I said it repeatedly: I will only ever photograph in black and white.

I said it emphatically: I will only ever photograph on film.

And then the day arrived that I came up with the concept for this series. And my long-held beliefs were obliterated by so much African dust.

So why the abrupt about-face?

I immediately imagined the photographs at night, with the unnatural, often garish and sickly colors of the modern human world. That was it. I would have to work in color for the first time. No choice in the matter. Furthermore, if I was going to photograph in color, then I wanted to embrace it, to not be frightened of it, to use the colors as expressively as possible.

As for switching from film to digital, given what was going to be involved technically, there was no choice in the matter.

Not only had I never photographed in color before, I had also never shot digital, never used lights or flashes, or even photographed at night. I was simultaneously excited and scared. Which, I feel, is a good place to be when launching into any new project. Get out of your comfort zone and dive in head first.

(& How They Got That Way)

essay by nick brandt

essay by nick brandt

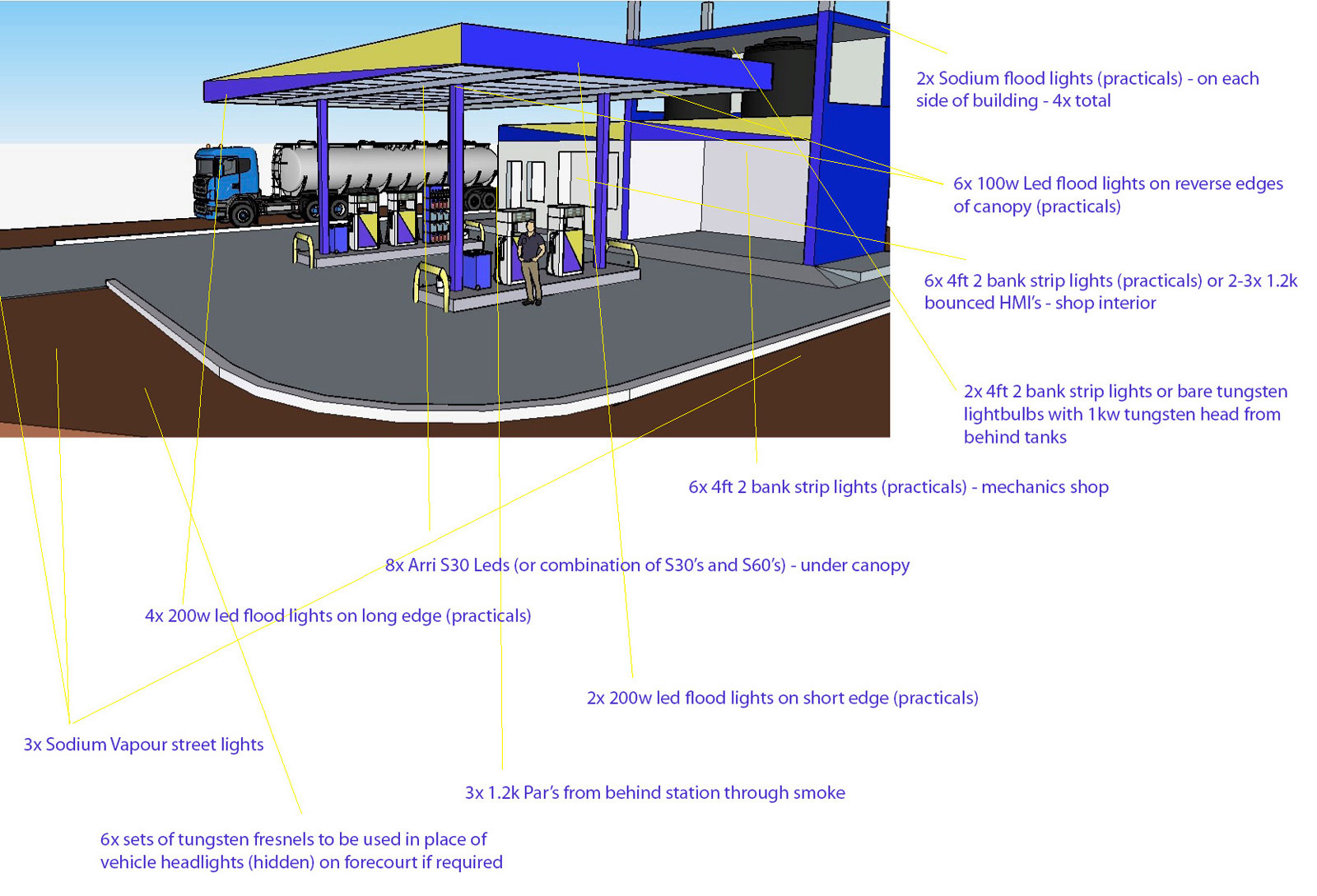

In reality, every element - from the bridge construction to the petrol station to even the forest - was built for the photos.

You may ask why on earth I would choose to build these sets, rather than just photograph the animals in one location and match it to a pre-existing location elsewhere.

Photographing - as much as possible - the reality of what’s in front of you is always the best approach. There are some obvious technical reasons: the different elements integrate organically. They naturally line up in terms of matching lighting and focal length. But I also find that this approach helps produce a superior end result emotionally. When you have as many of the physical elements as you can in front of you, new ideas, unexpected incidents that you would never have thought of, reveal themselves whilst photographing.

The biggest threat to the natural world is the encroachment on the remaining natural wilderness by humans and their out-of-control development, animals being wiped out in the rapidly decreasing number of places they can live. What you see in these photos is pretty much what has happened, is happening, and will continue happen across most of Africa in a frighteningly short number of years.

So my plan for the series was to photograph animals in the places where they still cling to an existence, and then with the camera locked down in the exact same position, build sets related to this human invasion, to surround the animals now trapped there.

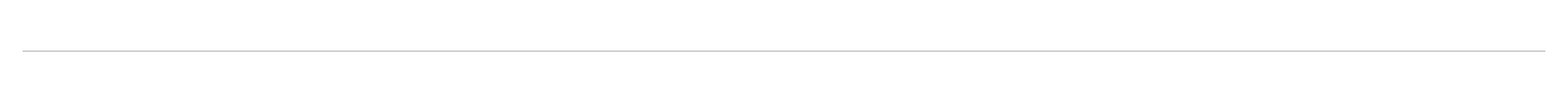

The sets, and their accompanying lighting, were designed before any animals were photographed in those locations. So when, for example, an elephant was photographed in the trench in front of the new petrol station, it was illuminated by lighting that would match the petrol station set still to be built: the florescent lights on the petrol station roof, the headlights and red tail lights of surrounding vehicles.

I always knew that it would take a long time for the wild animals to grow accustomed to the new objects in the landscape, and especially to get used to the lights all firing as the animals approached the camera. So photographing one set/location at a time was not an option. In that scenario, me and my crew would be stuck there for years.

The solution: I would have to plan, to buy and build everything in multiples, 10 sets running simultaneously on different locations. Months of technical research, preparation and testing ensued, the enormity of the undertaking becoming more apparent by the day.

The cameras — ten of them — had to photograph frames as rapidly as possible to create an instant panorama, so that, like Inherit the Dust, the final prints would look excellent blown up to 3+ meters in length.

Every set required multiple stands and scaffold towers with flash units. Whether it was the gaudy light radiating from the interior of a bus, the sodium orange glow from a row of street lights, or the flare of construction lights, the accompanying lighting was always carefully planned to match what would come afterwards on the exact same spot.

I knew that the equipment had to last several months in the field. Even with the use of flashes, the power requirements for the lighting was enormous. Everything at each location had to run off heavy duty car batteries that in turn were charged by banks of solar panels on scaffold towers.

In turn, this meant that all the electric cables had to be buried underground, sometimes running huge distances in steel piping, to make sure that the always-curious hyenas didn’t chew through the cables. Meanwhile, above ground, with the months of exposure to dust and potentially rain, the hundreds of flash lights had to be sealed with their electronics in plastic containers.

IntRAnet (not internet) dishes had to be set up at every location, so we could check on each camera’s

progress from up to 12km away from our base camp, and to be able to remotely adjust aperture and shutter speed.

Waterholes had to be dug at every location, the only way of encouraging the animals to approach the cameras. But since thirsty elephants could drain a waterhole in a matter of minutes, the waterholes had to automatically refill, via elaborate underground plumbing, from 5000 liter water tanks positioned some distance away.

Multiple motion sensors had to be connected to the cameras and positioned so that if and when an animal came in, they would trigger the camera shutter. I had never used motion sensors to take photos before, which inevitably leads me to an irritated aside….

In the past years that I photographed animals in Africa in the wild, I would spend weeks getting close to specific individuals that attracted my interest, gradually allowing them to become comfortable in my presence, waiting for them to present themselves for their portraits.

But much to my irritation, there had always been people who thought that I just used camera traps or remote cameras to achieve these photos. Now here I was, albeit out of technical and practical necessity, using the very thing I derided people for accusing me of using, in order to capture a key element of the final image. Irony indeed.

After extensive scouting of possible locations for each set, the first ten locations were chosen - either for their setting, or because they seemed a likely spot for the animals to frequent.

Andrew, my phenomenal ‘photography assistant’ (a completely inadequate job description to encompass everything that he did), and Jamie, my second ‘photography assistant’, spent long painstaking hours in the field with their own assistants setting up everything. With all the elements involved, readying each set would take them a few days. We rushed as fast as we could, to give the maximum amount of time for the animals to acclimate to everything.

(Take 1 : Getting it Wrong)

Across the range of locations, almost no animal of consequence appeared on camera. Via crude field camera traps set close by, we saw just how close they came without actually coming in. Porcupines, serval cats, the occasional hyena, wandered in, but not a single elephant, lion, giraffe, zebra…

It was now July. We were now two months closer to the advent of the seasonal rains. Once those rains came, it would be game over. So great is the erosion of the topsoil from overgrazing in this part of the ecosystem that just one short rainfall would be enough to shut down production. The vast tracts of powdery dust would almost instantly be transformed into a quagmire of gloopy mud, trapping anyone foolish enough to try and drive their vehicle through it.

To make matters more complicated, the ground in the second stage of shooting, with full sets and cast, had to exactly match the dry ground of the first stage with the animals, so that everything in the shots blended perfectly. A mismatch of dry and wet, and the whole concept fell apart.

We were now in a race against time.

One by one, as fast as the crew could work, the eight out of ten set-ups that weren’t producing results were dismantled and the land returned to how it was. The embryonic sets, the waterholes, the elaborate lighting setups, the solar panels, the intranet, the bloody everything, had to all be built again in new, hopefully more productive locations.

We were effectively starting again from scratch. Now a new set of animals had to get used to all this strange new man-made stuff in the landscape. But the dry season was now fully set in. Perhaps our waterholes would at last become enticing.

One morning in camp, we downloaded the overnight photos from one of the cameras. And halle-bloody-lujah. At last. Elephants there in frame, in the set. Lots of them. A profound flood of relief. Maybe the concept was going to work after all.

Now, other cameras in the new locations began to produce results. It was amazing to see just how small a waterhole needed to be. As the animals triggered the motion sensors, and a barrage of lights were triggered, most of the animals, especially the elephants, just took it in their stride.

In fact, once the elephants found a waterhole - sometimes following long water trails at dusk that we had created for them with our water truck - there was actually no stopping them.

On the very first morning of a new location, an elephant mother and baby in Bridge Construction with Elephants & Excavator walked over the fresh bulldozer tire tracks imprinted in the earth right in front of camera. Bingo.

In fact, multiple bingos. The elephants were now coming down every night into the deep trenches we had dug. It had clearly taken time for the animals to feel comfortable enough to descend. As always with anything to do with animals, patience was key. These images of the animals in the trenches were pivotal to the project, images that looked like were being swallowed up by the earth, or in an early grave, whilst man’s invasion, gathering pace, loomed over them.

However, the sudden change in fortune was not universal. On a few other locations, there was still next to nothing showing up.

The very first location that we had set up in May was in a dry river bed. Five long months of hyenas and guinea fowl but little else. I was ready to give up. Then, just two nights before we were due to break down the lighting, out of nowhere, the first elephant appeared on both camera angles. A female elephant with long, beautiful tusks, leading her calf down the river bed to our waterhole. This was River Bed with Elephants and River Bed with Elephants & Building.

Also back in the first couple of weeks, we had built a forest of dead whistling thorn trees, sourced from a location three hours drive away. The trees were carefully ‘planted’ to camera, so that none overlapped with another. The hope was that elephants would walk down a corridor of open space between them.

We waited for five months. One evening, a gazelle walked in, (Whistling Thorns with Gazelle), a lone figure in a desolate world, but elephants? No. Never happened. Almost. But not quite. The set was too close to the swamp two kilometers away, too close to the road, too close for the elephants to consider walking through the corridor of trees to grab a sip of waterhole water.

In the end, we built another forest of dead whistling thorns. This time in a dried-up dam close to one of our waterholes that the elephants had grown familiar with. As it turned out, too familiar. On the very first night, they seemed to take great pleasure in knocking down almost every one of the trees. I think I took that with surprisingly good humor, all things considered....

In the past, taking portraits of animals in the wild, I always looked for the photograph which appeared as if the animal was posing for their portrait in a studio, as if I was taking a portrait of a human (for me, there has never been any difference).

With this project, I had to single-mindedly discard this whole aesthetic, this way of thinking. I had to reject images of the animals in beautiful ‘noble’ poses that would normally have delighted me. Within the context of this concept, such images would have been emotionally and aesthetically wrong. Basically I had to reject that which was regarded as conventionally good

By contrast, the animals in this body of work needed to appear to be (even though in reality they were not) under threat, trapped, anxious, rendered immobile, at best melancholic.

Eventually the time came when I really had to start photographing the second stage of the photographs - the main sets of human encroachment and their human occupants. It was a hard choice when to give the go-ahead. What if I continued with the first stage of shooting for just one more night? Would I finally get that leopard, or a cheetah? But it was now mid-August with only two months until the expected rains. I couldn’t risk it.

The petrol station was the first to go up. Within a matter of days, it was finished. The lighting crew arrived from Nairobi. The multiple flash units used to light the animals were taken down, and in their exact place, film lights went up.

And so began the building of the main sets, all incredibly difficult given the remote dusty locations. Naia, my wonderful, passionately committed Spanish art director who had worked on Inherit the Dust, began, with her large art department crew from Nairobi, to construct the sets in record time.

Shooting in the middle of nowhere, in such harsh conditions, I marveled all the more at how films like “Lawrence of Arabia” were made, decades before the existence of cell phones and email. I lost track of the number of times we would have been screwed on set, unable to start or continue shooting, were it not for the existence of cell phones (which unlike in America, work almost everywhere, in the most isolated unpopulated areas - genuine life-savers).

And so, with the countdown to the rains approaching fast, we began to enter....

(not recommended for general mental health)

Two straight months of night shooting in relentless dust storms:

This is not an activity that I would recommend long term. Brutal for the crew, and brutal for those like myself who even if crashing into bed at 4am, will still stir groggily awake just a few hours later. Repeat, night after night, for two months. Concentration and energy levels drop precipitously, whilst crankiness rises exponentially. But with the pending rains and with the sheer cost of keeping crew in camp whether working or not, there was no choice.

Each night’s shoot was in itself especially challenging, due to the great waves of dust that blasted through with grim regularity, and invariably in the direction of the lens and our bloodshot eyeballs.

Sometimes, I would only manage to fire off a few frames before the camera lens was once again covered in dust.

My chosen method of working made these nights longer, and thus worse:

I would deliberately only loosely pre-plan the staging of the extras. I found that if I set everyone’s positions and actions too precisely, the people would look too stiff, and the whole scene too staged and posed. It always worked better to place the people in approximate positions, and leave them to talk amongst themselves, get comfortable or bored as the evening went on, but for them to be completely unaware of when I was photographing them.

Initially the featured people were all from nearby villages and settlements. But I wanted a more diverse representation of Africans. The whole point of the concept is that many people are victims of environmental devastation like animals, frequently living lives over which they have no control. So I started bringing in more people from Kibera, a poor area of Nairobi. Coming from a mixture of tribes from across Kenya, they gave the photos more of the variety that I needed.

Naia and her art department now began to build set after set in quick succession, sometimes two simultaneously. Amazingly, they managed to get the bridge construction set erected in less than a week.

Amidst all the stressful expense of elaborate sets, lights and everything else to create these photos, on the very occasional quiet day in production, I would drive out with just Kamete, my Kenyan assistant, to photograph elephant families as they moved across the plains to drink in the swamp. My camera would record the GPS coordinates of each photo, so that later, we were able to go back to where a photo was taken and find the exact spot by aligning the bushes and horizon. We then brought in a few of the local people whose faces most interested me. Standing to one side of where the elephants had been, an echo of emotions, in contrast with the other photos, it was simple and painless to execute. (Elephant & Human Family; River of People with Elephants in Day).

AND THEN THE RAINS CAME

I had been pushing the crew to the limit. We had been working for months, long hours, few days off. I knew that when those rains came, it was over. And boy, was that true....

On the very last night of shooting on location, as we were shooting the final frames at about 2am, big fat drops of rain began to fall, exploding on the ground in puffs of dust.

The next morning, the rain came down hard. Sure enough, everything was instantly shut down. No-one could move. The camp and sets were almost instantly flooded. That was definitely that.

The shoot wasn’t quite over, however. I had not been able to get any shots of leopard or cheetah. I really needed rhino, especially given their critically endangered status (due to the relentless poaching for their horns, all because of the misguided belief amongst some old men in the Far East that it would help with their failing erections.)

However, with rhinos now inhabiting only areas with an extremely high level of security, I was only given permission to photograph the rhinos in the presence of their rangers, on a private reserve in northern Kenya. This was fine by me, as I ended up photographing two wonderful rhinos - one blind - a 10 year old named Alfie, the other an adorable 2 year old orphan - with set elements in place around them.

In the end, for practical reasons, for six of the 45 shots in the series, we had to come back after the rains and shoot in two different locations to where the animals had been photographed, and match the locations. But for the vast majority of images in this series, the animals, sets and people were all shot from the exact same spot.

Considering this was an environmental photography project, it was all the more essential that we do everything we could to minimize our impact on the land.

Materials from each set were recycled to build the next set, and then the next, and so on. Naia was ingenious in how she was able to re-use stuff that we already had. For example, the building set at the river bed was almost entirely constructed of modified parts of previous sets.

Bridge Construction Set after the rains….

HOME

(Is Where I Want to Be)

And then began the months of post-production on the photos. This is always my favorite part of the creative process - the editing, where you gradually, hopefully, watch your vision begin to form and cohere. To see if the concept actually, please secular god, works.

Now, I can’t tell if a photograph is really any good until I see it printed. And printed large. Like 40x80 inches large. Then I can judge. But really, nearly everything looks good to a degree back-lit on a computer screen. Print it up and look at it as a large two-dimensional image - that’s the test.

So every image in this book has been ‘print-tested’ at that size. The size of the reproductions this book are as large as you’re going to see in book form. But you’re still unable to see so much that you would see in much larger prints - all those faces in the buses, all those nuanced expressions.

“AMERICA DOES THE UNTHINKABLE”

But back to Donald Trump. Unavoidable, really. Back to Trump and his legion of his venal, craven enablers. Tragically, the impact of their toxic policies, and their profoundly irresponsible contempt for the natural world, spreads far beyond the shores of America.

The day after the US Presidential election, November 9, 2016, having expected the worst, at my request the production team in Kenya bought a stack of Kenyan newspapers reporting the result, understood by pretty much anyone outside of America to be calamitous for the rest of the world.

You can just make out one of these papers in Hyenas in River Bed. The front page headline reads, in Swahili, translated “WHAT HAPPENED”? In another photo, Bus Station with Elephant in Dust, a man seated near the door of the bus reads a Kenyan English language newspaper, the front page headline of which reads “America Does the Unthinkable”.

Sigh. Yes, it did.

IN CONCLUSION, YOUR HONOR....

By now, with the overview of what was necessary to achieve this project, I think that you will understand just why digital was the only possible way of shooting this project. I hope that the film purists, a group of which I have long counted myself a fervent member, will understand and forgive me my digital trespasses.

The point is, I will never make such absolutist proclamations ever, ever again (oh...wait...)

© Nick Brandt

© 2024, Nick Brandt. All rights reserved.