There are the two shadowy lionesses in what appears to be a roiling storm or a pride asleep with one assigned protection; the elephant and child as mythic and historical as any Madonna; the long march, like that of the Lost Boys of the Sudan, of animals across an endless plain; a cheetah in the branches of an acacia tree; the architectural surprise of a giraffe’s upper body exploding from the grass; and a zebra, unhumbled in a human doorway.

The animals are the subject; their natural world the frame.

The photographs of Nick Brandt are both beautiful and haunting. They come upon you in a flush of abundance that it is almost hard to recover from and impossible to be equal to.

When I first saw his photographs I grew very quiet, because Brandt’s reverence for his subjects was so immediately clear. I was very aware that Brandt both understands that there is a division between photographer and subject, and yet wishes deeply that somehow there wouldn’t be. He knows, as we all must, that it is this division that has wreaked so much terror in the world of his subjects. It will not be lost on anyone why this book is titled Elegy.

Much like Philo Farnsworth, the seventeen-year-old who invented television—which he envisioned while watching the rhythmic flow of wheat in the Utah fields he farmed—Nick Brandt believes in the power of images to move us. Farnsworth prophesied that if people in one part of the world could see people in another part of the world and see how similar we all were, there would be no war. Sheer idealism, we cynically say now, but if we condemn the highest goal of communion, what have we achieved?

Nick Brandt is documenting a world apart, and, though he knows in his soul it is a world disappearing daily, he is also sending up a song in his grief.

I have never been to Africa, and almost all the animals in this collection I have never seen in the flesh (those I have seen were certainly not in their natural habitat). But I am a person, like many, who gains insight by making comparisons. These photographs strike chords in me, resounding off prior images and those images’ attendant histories.

I start with my sugary elephant, one of the many pure gifts of this collection. The heavy rumble of his pace and the way the dust lifts off him in clouds. And how he seems larger than the mountains and the sky, traveling within his own shadow—the sun floating directly overhead. How did Brandt have the wherewithal to get that shot? (A question I have of many photographs.)

Perhaps he had already spent days or weeks or months with his mouth open in wonder. Or perhaps, as is the photographer’s blessing and curse, taking the animal’s picture was the only way for him to feel that he had truly seen what he had. We are the lucky ones, in that Brandt is driven not only to take these portraits but to share them. I look at that elephant and I think of sweetness—that fine powdered sugar—and of power—the thunder of the feet. Brandt’s elephant is a being with a destiny ahead of him, led forward by the soft ivory curve of his tusks. He is myth and he is childhood dream all at once. What is most amazing is to know that he is real—of blood and of bone, as we are.

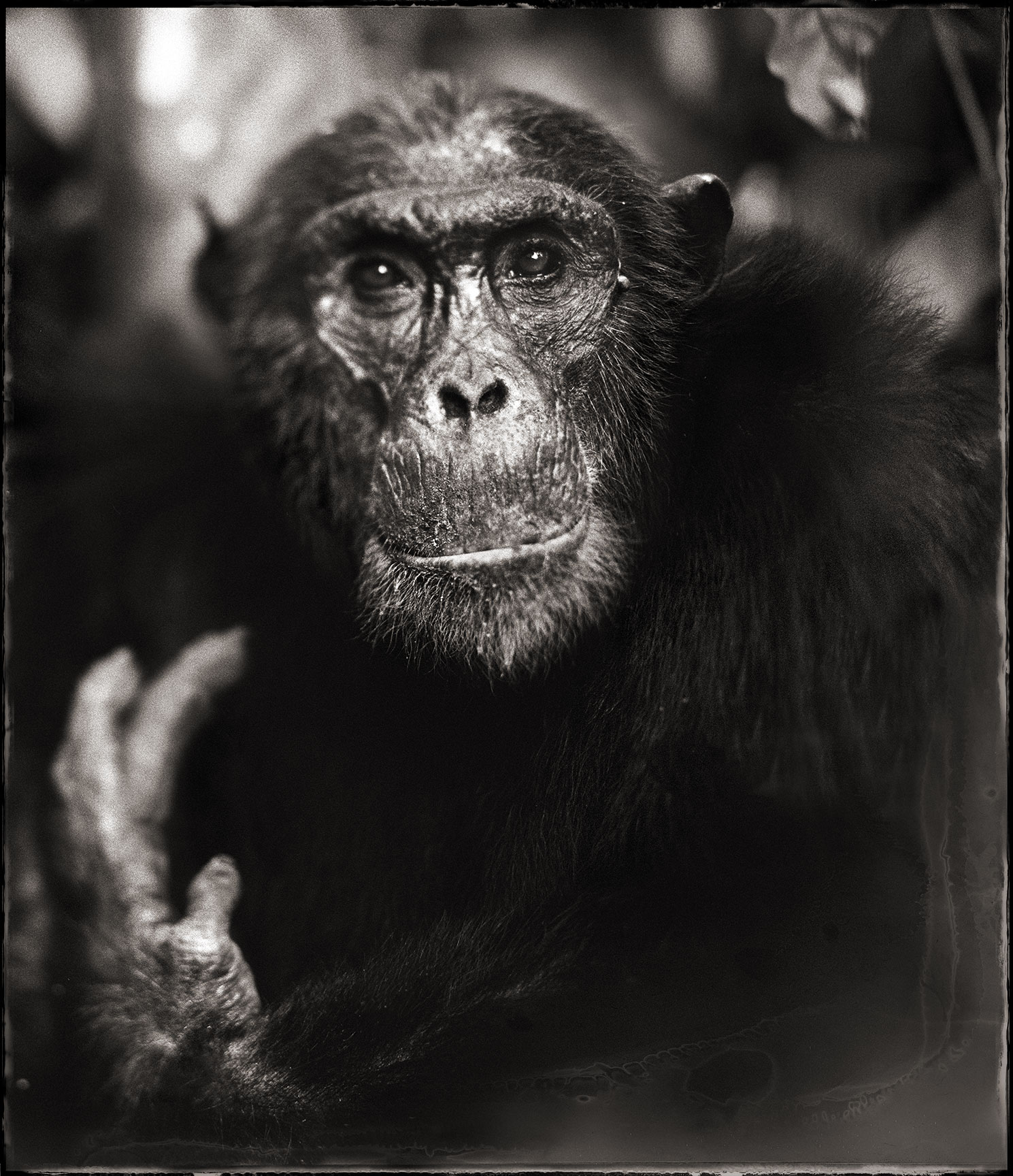

The profiles—the thoughtful zebra, the lions—both in close portrait and whole-body shots; the rhino with his incredible horns and his resigned, downcast glance; the three-quarter profile of the chimpanzee clutching his chest and looking off into the distance: these are just a few of what I would call Brandt’s portraits of military generals. Even the borders here often fade and burn the way old portraits of Civil War generals in the 1860s did. And the subjects’ eyes have the look of sacrifice and wisdom, determination and, yes, loss. Do I anthropomorphize them when I indulge in comparison? Guilty, yes. .And yet, in words I cannot hope to offer them as purely, as honestly, as unfettered as Brandt’s photographs have, I do see them as unwilling generals in a fight very different from that of bringing food home to their young. They are representatives that we now have before us to preserve their history, to make, perhaps, a last stand on the battle lines, to keep from destroying them.