This book is printed in Rhode Island, in the north-eastern United States, home of the saber-toothed tiger, giant ground sloth, and American cheetah. Also (ah, for a time machine), long before my time.

For each of us, wherever we live on the planet, animals such as these walked in the very place where we are sitting now. But - unless you are living somewhere certain to make me very jealous - most of these animals are long gone.

Meanwhile in parts of present-day Africa - albeit fewer parts by the day - sometimes even more extraordinary animals DO still roam.

East Africa. Where you can still cast your gaze across the plains, and see multiple species....

...elephants, giraffes, zebra, buffalo, gazelles, impala, hippos, lions, jackals, cheetah....

It’s the primal glory of such a land, shared by so many different creatures, that has a visceral impact on most humans that see this, that has the ability to fill the most jaded of us with a profound sense of wonder.

But the destruction of these animals, of these African places, is not happening in the past where we grew up, but in our own immediate present.

If we follow our present path of development and destruction, in just a few years time, rural African children will be as uncomprehending that elephants and giraffes once roamed the fields in front of their home, as we are that woolly rhinos once lived where our nearest shopping mall now stands.

Keep going at this pace, and the unique megafauna of Africa will be rapidly gone the way of the megafauna of America and Europe, which was wiped out by far fewer men, with far less technology, many centuries ago.

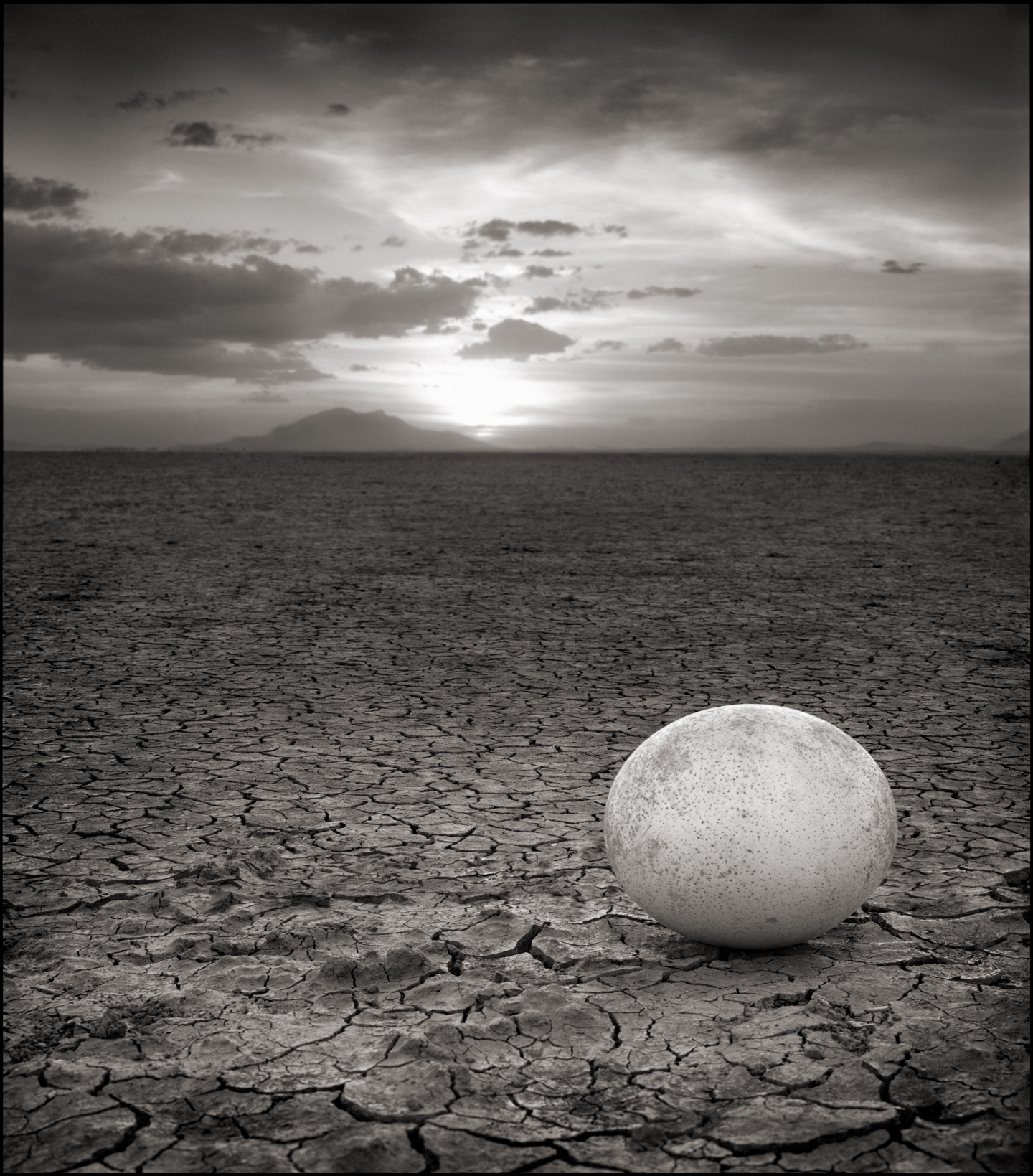

This was the genesis for this new body of work, Inherit The Dust.

Genesis. We are living through the antithesis of genesis right now. All those billions of years to reach a place of such wondrous diversity, and then in just a few shockingly short years, an infinitesimal pinprick of time, to annihilate that.

And East Africa is a microcosm of that. It just happens to be the microcosm where I photograph, and about which I know most.

However, perhaps the majority of us still think that the destruction here in Africa is to do with poaching, feeding the insatiable demand for animal parts from the Far East. Actually, as I’ve come to realize myself over the last few years, with a growing sense of foreboding, it’s so much more complex and monumental than that.

Mainly, it’s about all of us. Significantly, it’s about the terrifying number of us, and the impact of the very finite amount of space and resources for so many humans.

I conceived this project in early 2014 - to photograph life-size panels of animals in locations where they used to roam but, as a result of human impact on the environment, no longer do. Initially, I wondered whether I would find the locations that matched my pessimistic imaginings of a world in environmental disintegration. I was concerned that I might be exaggerating, overdramatizing.

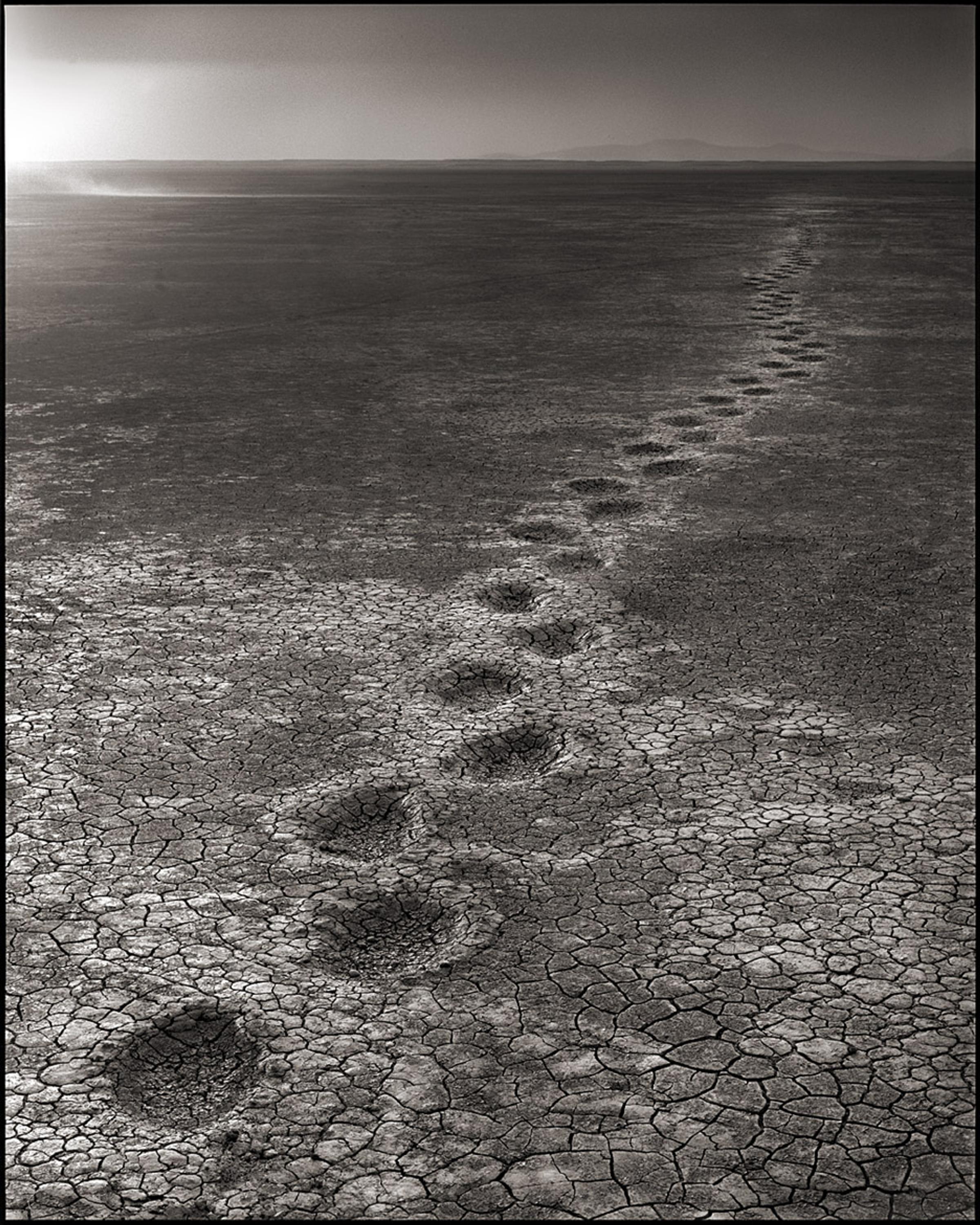

Over the years, I’ve driven through countless areas where just ten to twenty years ago there was animal life, but now has been relentlessly wiped out - sliced up and reduced to bush meat, leaving vast expanses of land devoid of any large mammals.

In many of those places, however, even the recent absence of animals in a landscape can still appear relatively undramatic. Of course, it’s only when you know what was there before that the loss is more keenly felt: the herds of elephants, giraffes and gazelles that not so long ago quietly moved across the plains and amongst the acacia trees, the heart-stopping sound of lions roaring on the still air at dusk and dawn. All deathly silent now.

There are many other places where the absence of animals is much more comprehensible, especially where cities expand outwards, or completely new towns and factories rise up. It’s in some of these places where I took the photos in this book. But when you look through the photos, they actually cannot begin to capture the sheer scale of man’s astonishingly rapid and escalating expansion into, and destruction of, the natural world.

The point is, by the end of the shoot, I realized that my concern that I could be exaggerating or overdramatizing was completely unfounded. In fact, just the opposite: how on earth to capture the real scale and speed of destruction in a photograph? I still don’t really have the artistic solution to that one.

As my crew and I moved from location to location during the shoot, I continued to be disturbed and depressed: Time and again, places where zebras roamed only two years earlier, now whole new towns had risen out of the ground at extraordinary speed. One of those places is in the photo, Road with Elephant, 2014. That scene may look like a town disintegrating back into the earth, but it is actually moving in the opposite direction, spreading upwards and outwards.

Frequently on the location scout before the shoot, I would select somewhere, only to return just four weeks later to discover it built up and out in such dramatic ways that it was quite fundamentally changed. In fact, the speed of development in this part of Africa reminds me of what I have seen in one other place in the world: China.

But then I had to stop and ask myself, am I just grieving for the loss of this world because as a privileged white guy from the West, I’ll never again be able to see these animals in the wild?

Most African people would say that our Western societies trampled all over our own natural world centuries ago in the interests of economic expansion, and that in Africa, they never got much of a chance to develop economically until now. And so now it is their turn to economically grow. Why should they be deprived of the comfortable, material lives that we have in the West?

In some regards, it’s a reasonable argument. But at what cost?

To state the obvious, protection of the environment and economic benefit do not have to be mutually exclusive. In fact, if you’re smart, they go hand in hand.......