MY LIFE IS LIKE A RIPENED BANANA

SURVIVORS: THEIR PAST AND PRESENT

zimbabwe

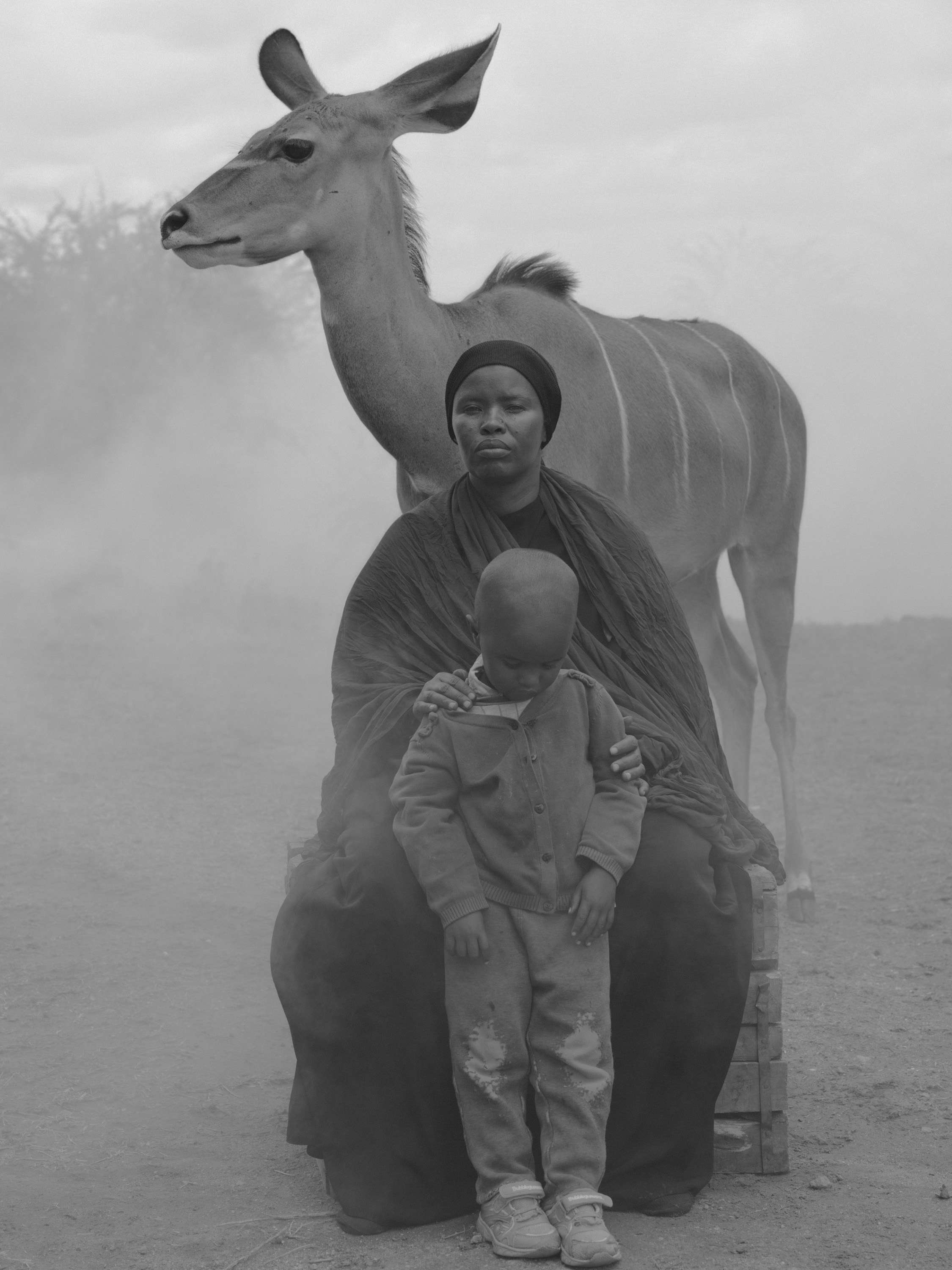

Clementia lives with her son John in the Victoria Falls area in Zimbabwe. It was a beautiful place when she was younger, but from around 2010, years of extended harsh drought have resulted in the forests drying out and crops failing. The wells are running dry, which means Clementia and other villagers have to walk further and further to find water. And with escalating deforestation, animals are forced into areas of human habitation, destroying crops and coming into conflict with the farmers.

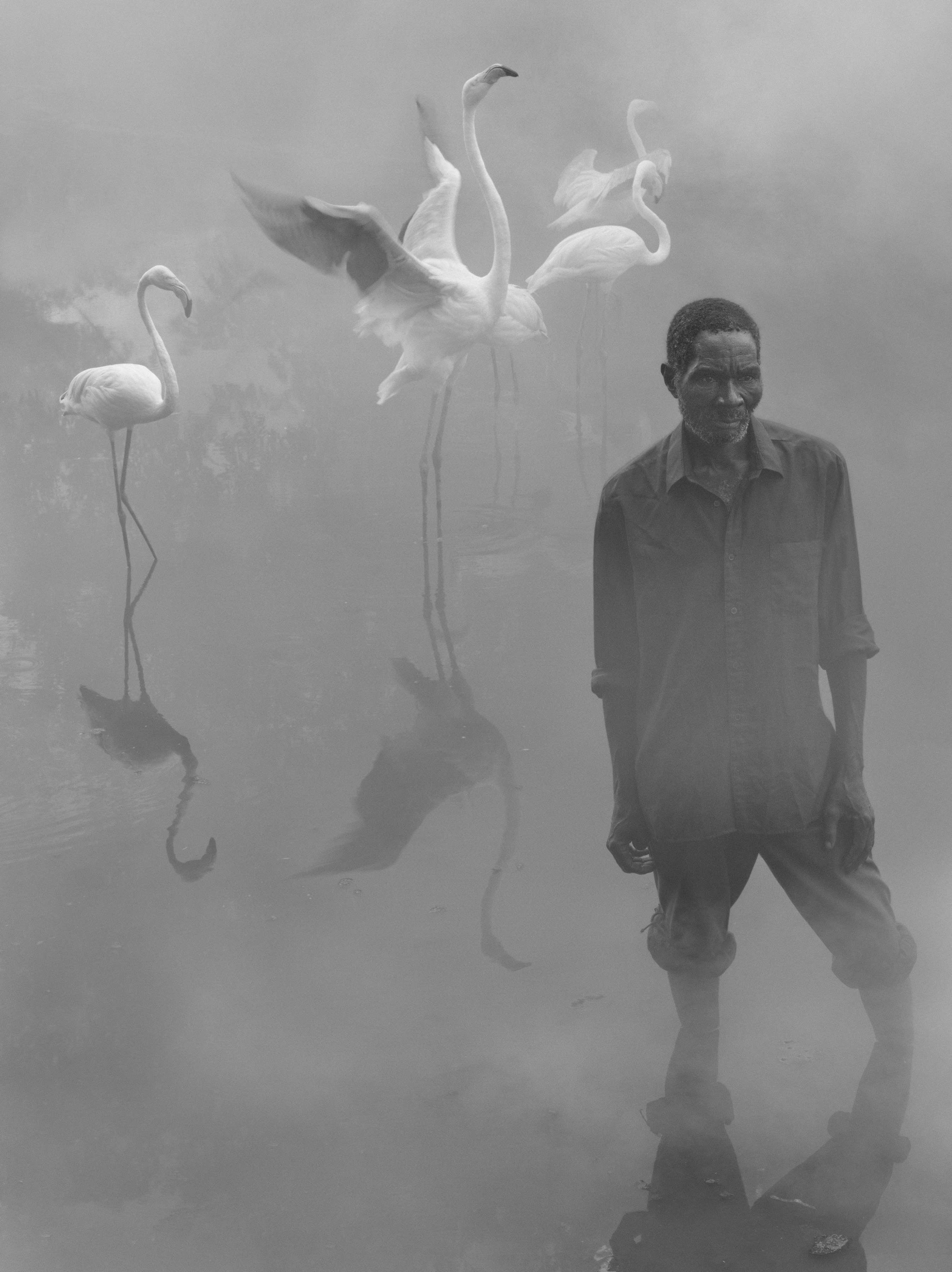

Silva was a farmer in south-eastern Zimbabwe. The rains that were once regular have so become unpredictable, and severe droughts so frequent, that Silva decided to relocate to Lake Chivero and start farming and fishing.

But over the years, he is now facing the same problem. At the lake, water levels have become so low that fishing is no longer a realistic option.

Helen has a small plot of land where she tries to farm maize, but because of the lack of rainfall and dried up wells, her crops have repeatedly died. In 2019, almost all her chickens also died because of disease. As a result, she has little food and lives in poverty.

For Jack and Regina, their only source of food is a small plot of land for growing vegetables. However, in recent years, their crops have failed, and with the worsening drought most of the local rivers and wells have dried up. This has forced them to go begging for water in surrounding areas. Sometimes they go for a couple of months with little food, forced to live off handouts.

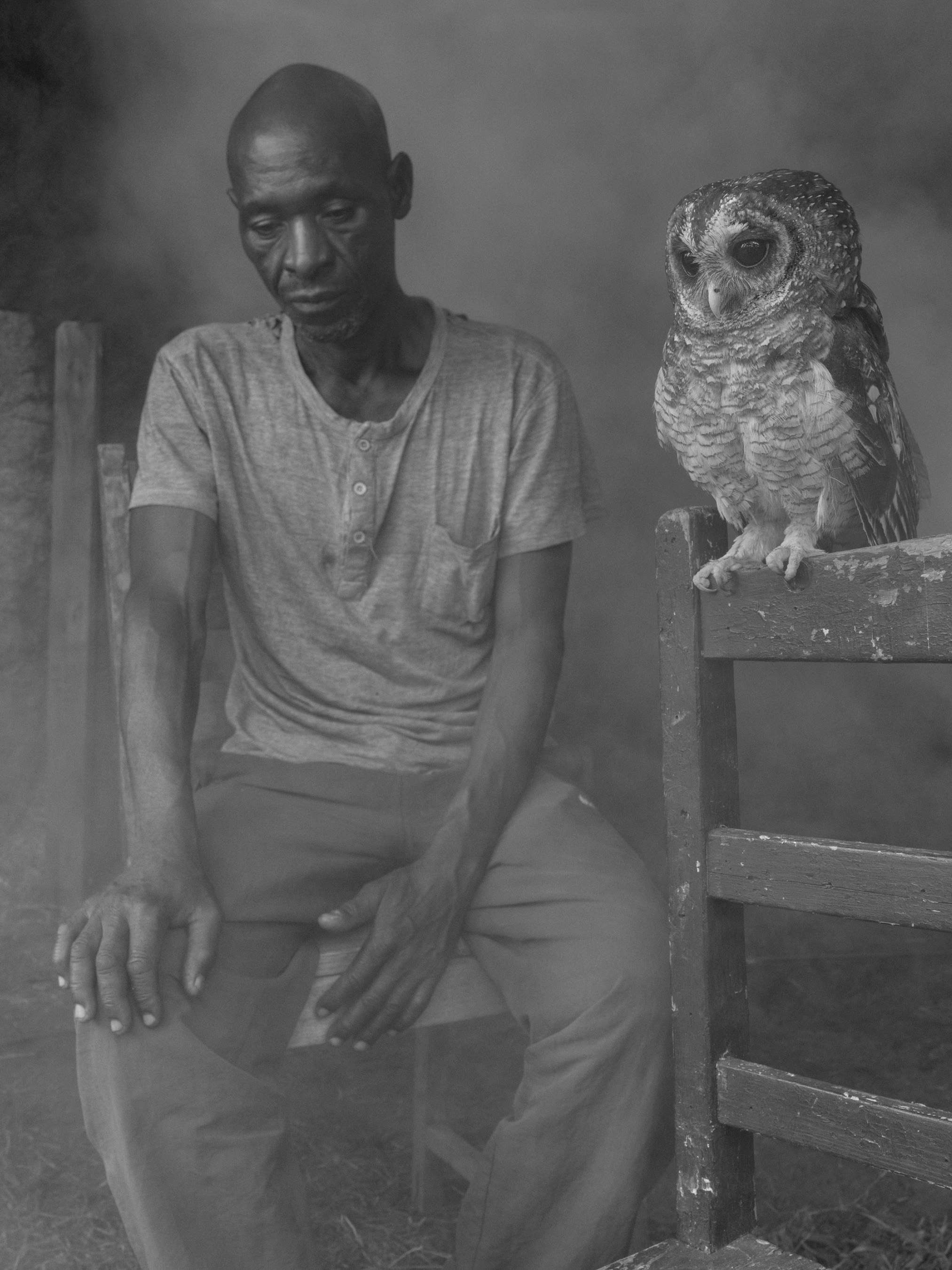

John and Margaret, who live with their nine grandchildren in central Zimbabwe, have a small farming plot. Like so many others there, the main challenge is not having access to water. The family walks 2km every day to collect water. Because of the prolonged droughts, their small farming plot remains unplanted. It has become difficult to feed everyone, so even in their old age, they survive by doing manual labor jobs.

Their granddaughters, Lene and Shyline, have been looked after by John and Margaret for most of their lives. Their mother passed away when they were very young, and their father subsequently abandoned them.

It was March 31, 2019. The heavy rains and winds came unexpectedly. And then Cyclone Idai.

Kuda’s family lived in a low-lying area in eastern Zimbabwe, so they were the hardest hit. The floods and avalanches destroyed everything in the village. Kuda, her husband, and three children were all swept away. Kuda managed to swim and reach her home, but the cyclone had destroyed everything. Six months pregnant at the time, Kuda suffered a miscarriage. Two of her children were never found.

Currently, Kuda, her husband, and their one surviving child are living in a makeshift camp for displaced people affected by the cyclone. When interviewed about what happened to her, a year and a half later, she said not to worry about her. She said that nowadays, “my life is like a ripened banana.”

Cyclone Idai was a terrifying harbinger of what climate change will bring in the coming years: more frequent high-intensity storms. And with that, of course, more destruction.

Before Cyclone Idai hit, Luckness was employed and lived an uneventful life. But the cyclone destroyed her house, and she and her two children were swept away by the waters. One of her two children suffered a spinal fracture, which has left her permanently disabled.

Currently, Luckness and her children are living in a makeshift camp for displaced people affected by the cyclone.

Cyclone Idai was a terrifying harbinger of what climate change will bring in the coming years: more frequent high-intensity storms. And with that comes, of course, more destruction.

Matthew grew up near Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe. He says the place was beautiful when he was younger, but from around 2010, years of extended harsh drought have resulted in the forests drying out and crops failing. His livestock also died. It has become hard for him to afford to send his children to school.

Even wells are running dry, and with that, the need to walk further each month to find water. And as deforestation continues apace, animals are forced into areas of human occupation, destroying crops and coming into conflict with the farmers.

Patrick has been a fisherman in Zimbabwe for 5 years, but the declining water levels in Lake Chivero is now making it difficult for him to continue fishing. The fish catches for the day have dramatically declined. Patrick is also a farmer, but again, the ongoing drought has affected his crops.

Richard lives with his wife and children in eastern Zimbabwe. Originally, a maize farmer and cattle owner, extended droughts from 2010 onward began to dramatically impact his livelihood. He drilled a bore-hole, but it has since run dry. So, he turned to farming tobacco as a way to survive. Richard used to own fourteen cattle. But because of the drought, all the cows have died from disease. Richard now struggles to provide for his family and is unable to send his children to school.

Richard feels that the reduction in rainfall has been caused not just by climate change, but also by the clearing of forests for the production and curing of tobacco, which has left vast stretches of forests in the area barren.

Shepherd, a horticultural farmer in eastern Zimbabwe, made a good living and was able to send his children to good schools.

But on March 31, 2019, Cyclone Idai hit, and everything changed. Shepherd and his wife and three children lost everything. Their home, crops and livestock were all swept away by the cyclone. Even his borehole and irrigation system were destroyed.

The family relocated to Harare in the hopes of building a new life. But they now survive hand-to-mouth, selling wares in Harare and relying on the kindness of family members. He still hopes that one day, he will be able to go back to his village and farm again.

Thomas and his wife Monica have been small scale farmers in Zimbabwe for the past 10 years. But because of the extreme drought, for the last three years they have found it very difficult to survive. Their well is now dry, so they have to walk 5km to fetch drinking water.

Thomas can operate a tractor with a ripper, but everyone is in the same situation: no-one wants to gamble using a tractor to prepare the land if their crops fail from drought.

Halima’s husband left her, and so she and her children had to move south to Nanyuki. She is now forced to do menial jobs to raise her kids.

Finally, he gave up all hope, and moved to Laikipia in 2017 to start life again.

To this day, he really struggles because he has nothing there. The education of his two children, and even food, is now a problem.

Moraa had been in college at the time, but was forced to move to Nanyuki where her aunt lives, and where she now works in a shop to make ends meet.

Nuria left her home in the central highlands of Kenya, and moved to Nanyuki, where she now rents and does laundry.

Robert and Nyaguthii now work as casual laborers in stores and warehouses.

Both their children were swept away in the flooding. They have never been found.

They were forced to move to Nanyuki, where life has been a real struggle, a hustle, finding menial jobs. Samuel says “I don’t even like to remember where we lived before —it’s too upsetting.”

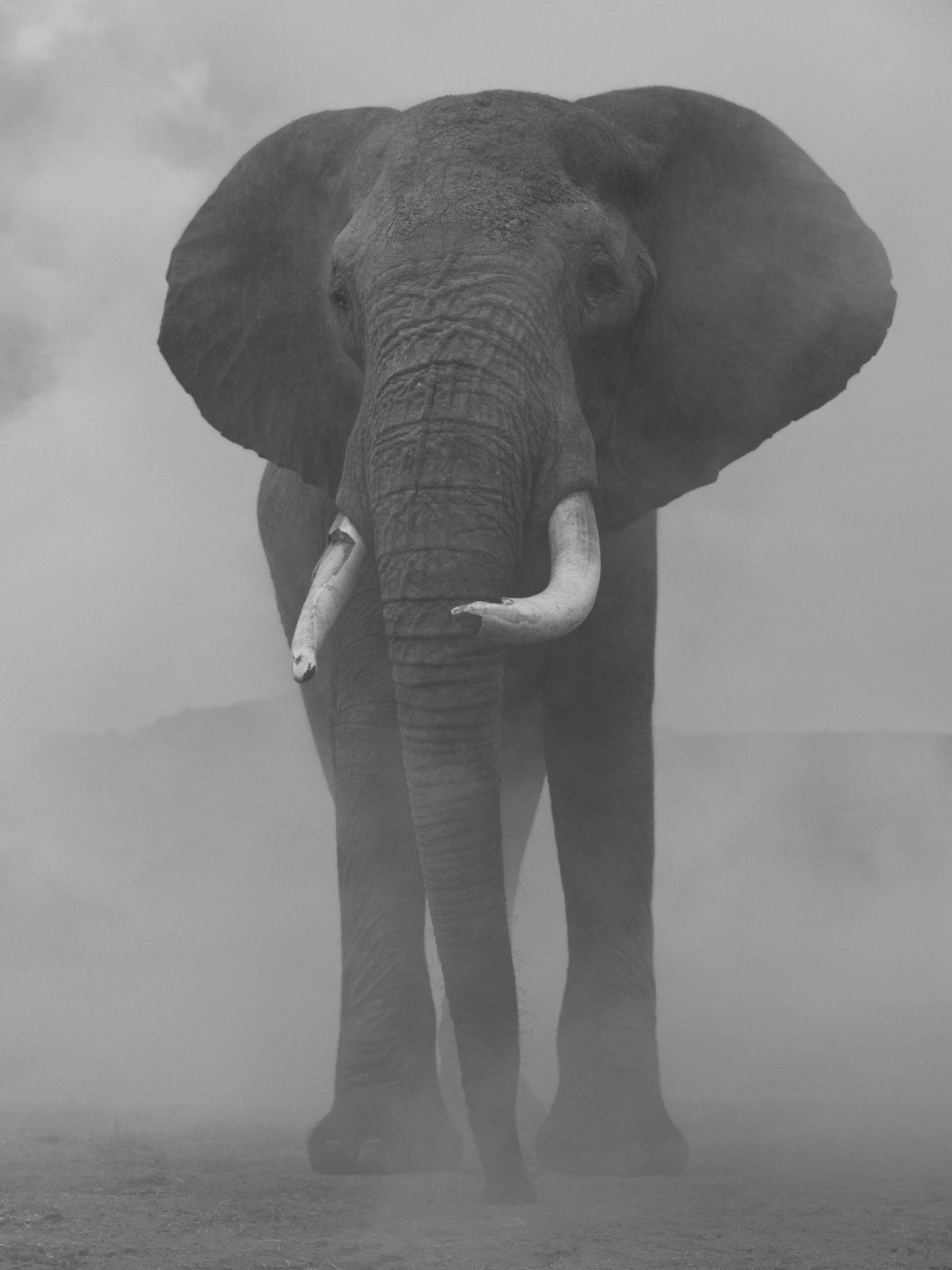

Zimbabwe has the second highest population in Africa, perhaps 65,000 as of 2020. However, since 1965, the country has engaged in the periodic culling of elephant herds, families, and individuals, due to what is regarded as an excess population.

Once upon a time, there would have been no such thing as an “excess population,” because there would have been enough land for them to roam and migrate. But with habitat loss and destruction, and human encroachment, this forces elephants into the remaining uninhabited areas, resulting in severely damaged woodlands from overgrazing. And then the culling begins.

Teresa and Samuel used to live and farm in the central Highlands of Kenya. But in 2016, after three months of constant rain, landslides from the flooding covered and destroyed their house and killed their livestock.

They were forced to move to Nanyuki, where life has been a real struggle, a hustle, finding menial jobs. Samuel says “I don’t even like to remember where we lived before - it’s too upsetting.”

With climate change, the situation becomes much worse, as vegetation and woodland dies off and burns, and humans and wild animals search for what remains.

Bupa and another elephant, Jackie, were 8 or 9 years old in 1989, when they were rescued from a culling project in Zimbabwe by the owner of Ol Jogi Conservancy in Kenya. Their parents would have been killed.

Bupa and Jackie bred at Ol Jogi and had a daughter, Meisha. Jackie died from a viral infection in 2019.

Kudu are declining in population across areas of sub-Saharan Africa due to illegal bushmeat poaching, habitat loss and deforestation.

Across the continent, the zebra population is in decline, reduced an estimated 25% over the years 2002-2016. This is partly due to bushmeat hunting. As poor rural people struggle to survive in an ever more harsh landscape compromised by climate change, this forces them to turn to bushmeat hunting. However, in some areas there is also industrial-level hunting, destined for meat markets in towns.

The decline in zebras is also because of rapidly disappearing habitat due to human encroachment and loss of grazing to a growing number of livestock. Nowadays zebra, once a common sight across African plains, are mainly only found in protected areas, from which they frequently migrate into unprotected areas, putting their lives at risk.

14 years old when photographed, they have had healthy lives with daily walks. In March 2021, Diesel died aged 15, a grand old age for a cheetah, whose average life span is 10-12 years.

The current situation for cheetahs in Africa is stark: driven out of over 90% of their historic range, the population across the continent is down to less than just 7,000 in 2021. At the current rate of decline, cheetahs are heading toward extinction.

As ever, habitat loss is one of the main reasons. With that also comes the decline and disappearance of the species that they prey on, as those are killed by humans for bushmeat. Even in protected areas, cheetahs are in decline, partly because the animals need room to roam.

The two other elephants were eventually able to move up to Wild Is Life’s Zimbabwe Elephant Nursery in a park in the west of the country, near Victoria Falls. But because Kura’s leg was so damaged, it was felt that he would not be able to manage the rough terrain at the release site, or cope with getting into a fight with another bull. Meanwhile, Kura is very gentle with all the younger rescued calves, and a great teacher.

Zimbabwe actually has the second highest remaining population in Africa, perhaps 65,000 as of 2020. However, since 1965, the country has engaged in the periodic planned culling of elephant herds, families, and individuals, due to what is regarded as an excess population.

Once upon a time, there would have been no such thing as an ‘excess population’, because there would have been enough land for them to roam and migrate. But with habitat loss and destruction, and human encroachment, there is less and less land for viable habitat. This forces elephants into the remaining uninhabited areas, resulting in severely damaged woodlands from overgrazing. And then the culling begins.

With climate change, the situation becomes much worse, as vegetation and woodland dies off and burns, and humans and wild animals search for what remains.

And so we come to Mak.

It was 1986. Elephants were being culled in Gonarezhou National Park in the southeast of Zimbabwe. Mak’s mother was one of those culled. Mak, a very young, and now traumatized calf, was rescued together with three others.

As he grew, he became too much of a handful for his carers. That was why he ended up at Imire when he was about five years years old. (He was photographed here when about 35). It took many years to gain his trust, but now once granted, it is there for life.

The key, going forward, is to create and conserve trans-African migratory corridors, to allow the elephants and other wildlife to migrate between countries.

The pangolins rescued by Wild is Life, are generally rehabilitated after two weeks, and then released in collaboration with National Parks. However, It was too risky to release Marimba, as she had become so attached to her handler, Mateo. So she stayed. When the photo was taken, she was 13 years old.

Up to 200,000 pangolins a year are estimated to be taken from the wild in Africa and Asia, according to Wild Aid. This has made them the most trafficked wild mammal in the world.

Their scales, and even their fetuses, are used in Chinese Traditional Medicine, while their meat is con-sidered a delicacy in China and Vietnam. Due to this, the eight species officially range from Vulnerable to Critically Endangered.

Zimbabwe has very strict laws about pangolins and there’s been a lot of work done in Zimbabwe in terms of policing and border control for pangolin movement.

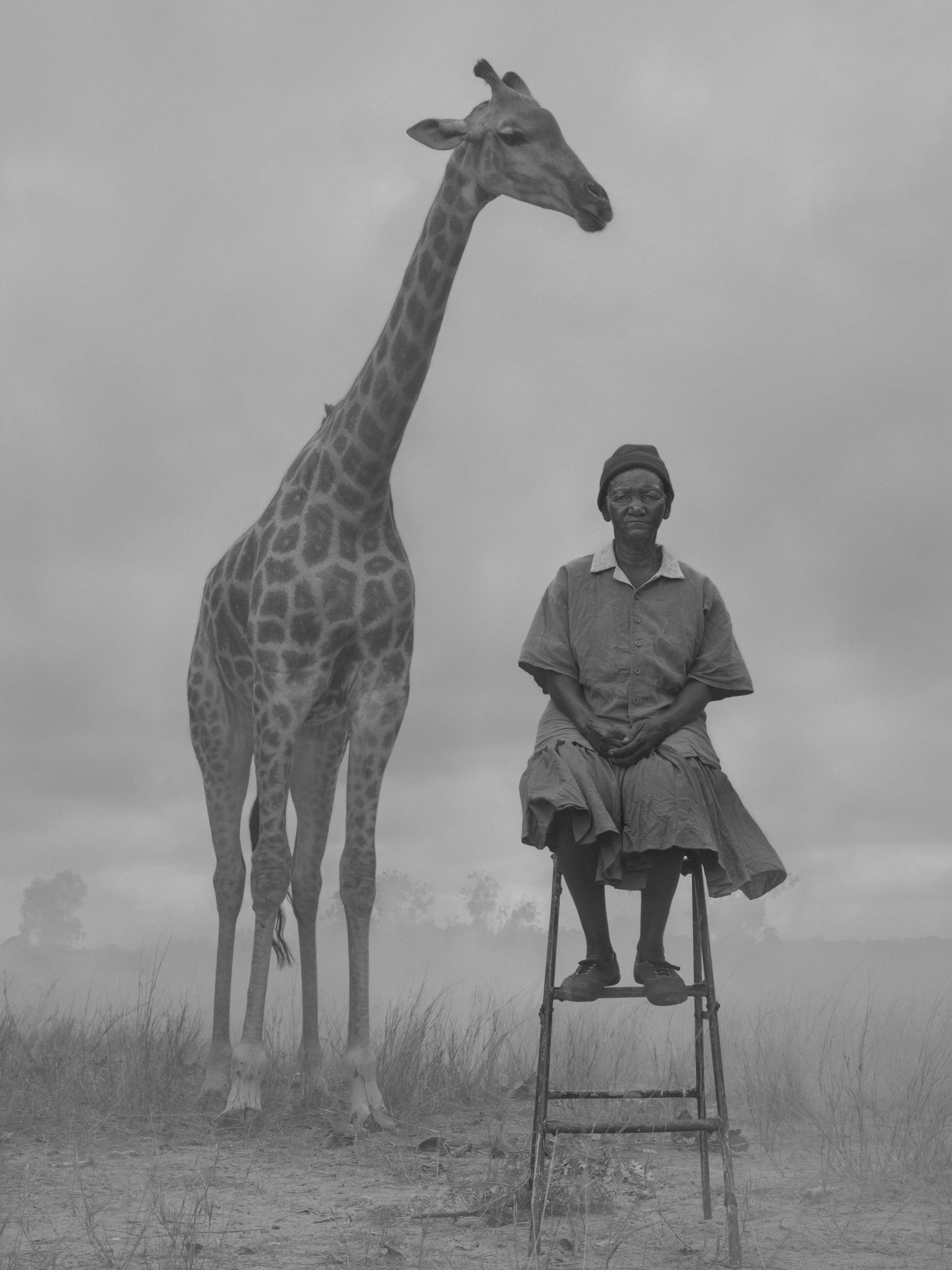

The southern African giraffe, of which, as of 2021, there are less than 30,000 remaining in the wild, is listed as threatened. Across the continent of Africa, there are barely more than 100,000.

Shockingly, in Zimbabwe, giraffes are not a protected species; hunting, the removal of animals and animal products from a safari area, as well as the sale of animals and animal products is permitted.

Najin and Fatu were both actually born in captivity, and had been living, along with two males, in Dvur Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic. In 2009, the four rhinos were moved to Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya in the hope that they would have a better chance of breeding. Sadly it never worked out. Sudan, the last male, died in 2018.

So now, complex in vitro fertilization procedures—never before attempted in rhinos—are conducted several times each year in a final attempt to keep the species from going extinct.

In the meantime, Ol Pejeta has around-the-clock armed security for Najin and Fatu.

Now, 25 years later, the other siblings that were released are still on the property. They fly around free, and every year, produce chicks. They’ve been caught in fishing nets multiple times, and so far eventually break free. But it’s a constant battle trying to preserve the wild bird life because of the fishing nets that are used in the lake.

Martial eagles are now officially endangered, also killed by shooting or poisoning, as they are unjustly regarded as a threat to livestock.

As a result, Bateleurs’ range is mainly restricted to the big game parks. The rest have disappeared, and are now listed as endangered.

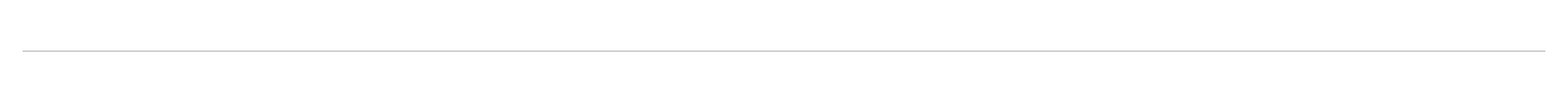

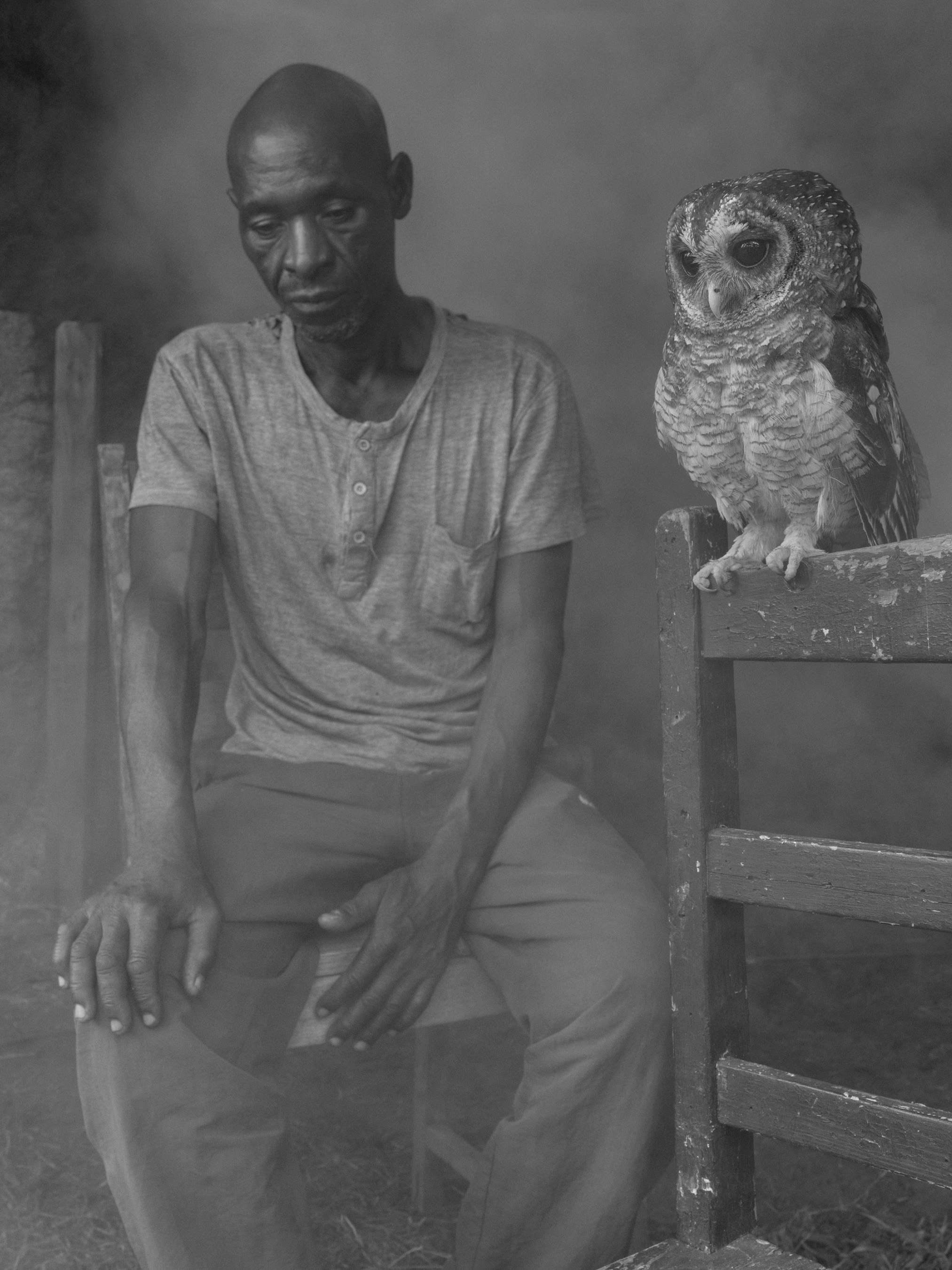

Giant eagle owls are actually widespread across sub-Saharan Africa, although perhaps declining in rural areas.

A major problem in many African cultures, but especially in Zimbabwe, is that the owl is heavily associated with witchcraft, especially those owls with horns on their heads. As a result, many owls are poisoned, shot, killed. So Matagat is now a kind of ambassador for his species, to educate the public.

This is typical of the situation across its range in Africa. It’s all about deforestation—the destruction of the crowned eagle’s habitat.

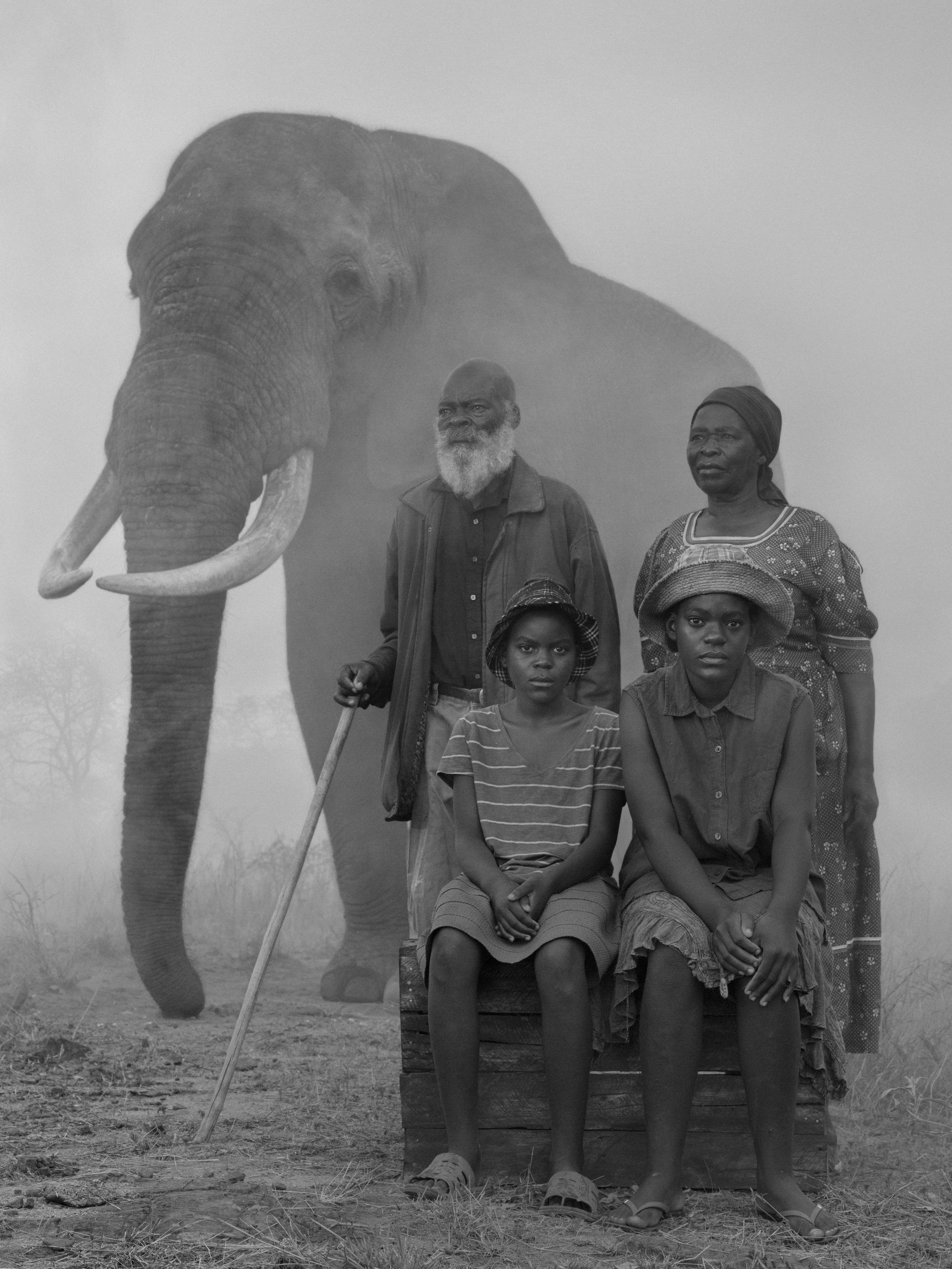

Lesser flamingos are declining as the number of breeding sites for them diminish.

Hooded Vultures are currently listed as Critically Endangered. Habitat degradation, persecution and per-haps above all poisoning are the main problems. Just one example from Kuimba Shiri:

in February 2020, a farmer poisoned the carcass of a cow in order to kill dogs (doubly horrifying). Out of a flock of 300 birds, over 50 vultures died. Kuimba Shiri managed to rescued, rehabilitate and release twenty one of those.

Kuimba Shiri has a number of rescued wood owls. Some saved after trees were cut down, and chicks were found inside, others rescued as a result of being poisoned.

With the poisoning, it’s the same tragic story the world over, and the reason for so many of the birds that come to Kuimba Shiri: Rat poison, a terrible instrument of death that makes animals bleed hemorrhagically, bleed into themselves and die. Every animal that feeds off those animals then is also poisoned. (And of course there is no need to use poison. If people must, they could use non-poison rat traps instead.)