Today

April 22, 2021

Earth Day

In news headlines: a brutal Covid-19 tsunami has landed in India and is creating an apocalyptic scale of suffering. The scandal, however, is not the pandemic; it is the nations of the world primordial hoarding of supplies and sending out of platitudes rather than helping humans in distress. In the same breath, a new American president, Joe Biden, hosted an e-Climate Summit where he committed the United States to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 52% below 2005 emissions levels by 2030. (Given the reality of the gross ineptitude of a world that fails the simple solidarity test that is the global Covid-19 pandemic, a forecast for a successful outcome of this happening is now downgraded to “unlikely.”) In the evening, a friend in Dar es Salaam called to tell me that a tropical cyclone named Jobo was bearing down on his city—a cyclone, in East Africa? In other words, the times in which we now live are no longer about proverbial canaries in coal mines; we are in the middle of a liminal epoch that is groaning to the soundtrack of a most unsettled earth.

I held an atlas in my lap

ran my fingers across the whole world

and whispered

where does it hurt?

it answered

everywhere

everywhere

everywhere.

—Warsan Shire (What They Did Yesterday Afternoon)

Today, April 22, 2021

Earth Day

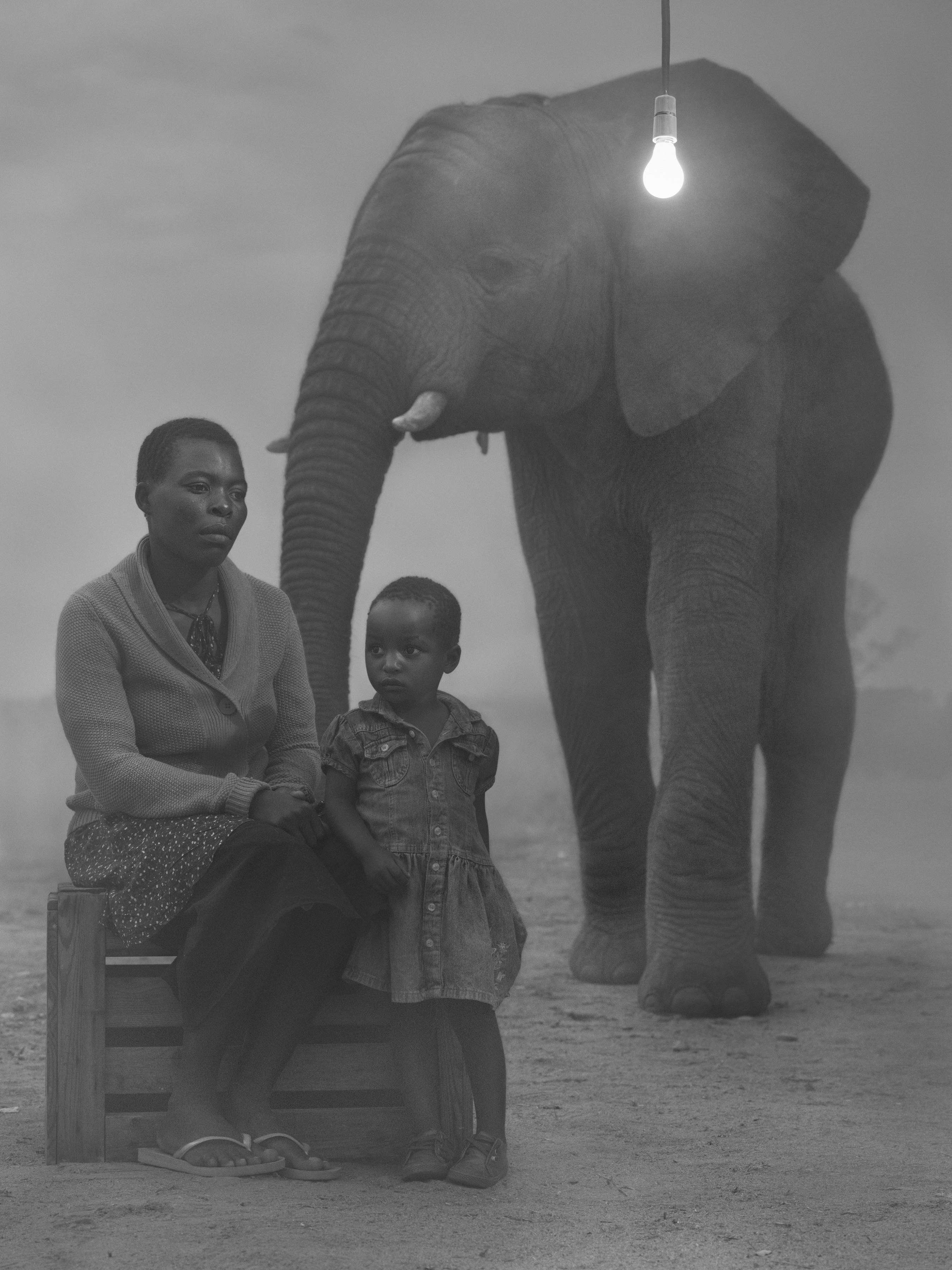

The prints from the series The Day May Break are here. There had been a five-week delay due to the always-changing Covid-19 rules and restrictions, the evidence of ongoing institutional bafflement and anxieties that masquerade as stern officialdom.